(sic)

The ironic thing about working in the hospital is that you're not allowed to be sick. I don't think I've called in sick to work once since I started medical school, and that was more than ten years ago. I missed work on the two occasions that I gave birth, of course, and last year I took a "personal day" to be with Joe was hospitalized in the ICU with myocarditis, but in terms of actual sickness, for me myself--nope. One gets the general impression that it's not really allowed. It's one thing if you need surgery or something, and being hospitalized probably would preclude you from being on the job, but when it comes to normal people sick, well, people in medicine just don't do that.

Luckily (and I know I must be jinxing myself here, but just pretend you didn't hear me say this) I have the immune system of some sort of oxen species, which I attribute to several months working the the Peds ER in my twenties and, at present, living in a house with two kids who more often than not aim all coughs for my face. So I don't really get sick for the most part, and even when I do catch something, it's nothing major that would prevent me from being able to do my job safely. (Luckily, I work in the OR almost 100% of the time, so wearing a mask at work is sort of part and parcel of my everyday routine regardless.) Still, I find it somewhat ironic that, working in the healthcare profession, the general consensus levied towards people who call in sick is somewhere between disbelief and automatic assumption of some sort of weakness in morale. Or more often, doctors themselves will just completely deny that they are sick at all, pushing themselves until they are sweaty and shaking and having weird fever dreams while trembling in a corner somewhere. Sick? Who gets sick around here?

Anyway, I'm not sick. Just sometimes I think of these things. You know, ironic things.

juggling

Before you ask: yes, I changed my picture on the sidebar. I just couldn't handle how smugly superior I looked in the other picture, like I was gazing down from my throne on high. (Granted, this effect was probably amplified by the fact that Cal took the photo--Cal, who necessarily takes every portrait shot from below.) But every time I opened my own page, I felt like there I was, looking down my nose at my own self for wearing knock-off Keds in seventh grade or something. Remember when people used to color in little blue rectangles on the heels of their canvas sneakers, to make them look more like Keds? Yeah, me too. So anyway, I switched the photo. The surgical mask is not some sort of stab at anonymity, by the way--after almost ten years on the web, I think the cat's out of the bag on that one. It's just that that's the most recent photo I have of myself and I happened to take it at work, so there you are.

(Cal just came in as I was posting up that photo, by the way, and the following dialogue took place:

CAL

Is that a picture of you?

MICHELLE

Yeah, that's me.

CAL

You don't look normal.

MICHELLE

I look abnormal?

CAL

Yeah, why are you wearing that doctor suit?

Anyway, ha.)

As most people with jobs in medicine (and as probably most working mothers regardless of chosen career) can attest--my day to day life is pretty stressful. Not that I don't love my job, but there are moments when I consider the wisdom of choosing a field where patients routinely try to die right in front of my eyes. In those moments, I can appreciate the allure of a field like, say, pathology. Meticulous attention to details, beautiful grasp of descriptive vocabulary, and that certain distance between you and your patients that can sometimes be a saving grace. Granted, I think most people think that anesthesiologists already have enough distance from their patients (for instance, we always have ways to stop an annoying conversation--a syringe of midazolam in one hand and a syringe of propofol in the other does wonders), but I think most anesthesiologists that I've met are fairly empathic and have a decent bedside manner--or at the bare minimum have perfected the fine art of small talk--considering that the majority of their job takes place while the patient is unconscious.

If I had to list the most stressful thing in my life though, it would not be my job itself. In fact, far and away, I would say that the most stressful thing in my life is the juggle of trying to figure out who is going to be home for my kids in the evening. As an anesthesiologist, my hours are somewhat more variable than Joe's. Some days I get out from work pretty early, and some days I get out from work pretty late, and though for the most part I can anticipate which ones the Really Early and Really Late days are going to be, there are many days in between that I just don't know whether or not I'm going to be home by dinner until it's pretty much too late to do anything about it if I can't. These are the stress days.

We have a nanny and she's wonderful, and while she doesn't cook, I usually do enough cooking on the weekends that she has plenty of options of food to heat up and serve the kids. This particular nanny has been with us for two years now, so the kids know her and love her, and she has no problem staying with them until either Joe and I get home, even if it's a little later than expected, so thank goodness for that. But there are days when I'm trapped at work, and I get a text from Joe that he's trapped at work, and I think about the evening ticking by with neither parent at home, and all things that need to get done when we do return--the bathing and the school lunch-packing and the bed-timing and all of it--and it just stresses me out.

Oddly, being at work late in and of itself is not stressful at all if I know that Joe is home with the kids. In that way, my nights on call are oddly liberating. When I'm scheduled to be on call, Joe tries to structure his day so he can at least be home before 6:00pm, and once he texts me that he just walked in the door, I can relax. After that point, it feels like it doesn't matter how late I have to stay at the hospital. A parent has has landed. My kids are no longer orphans. And strange as it sounds, there are nights at the hospital that feel less frenzied and less stressful that certain evenings at home.

This is not to make parenthood seem like this joyless dirge of endless food preparation and cleaning up in various forms (though...kind of), and not to say that we don't have fun when we are home. We do. But sometimes the time we have together seems so short, and so goal-oriented, so purpose-driven. I wouldn't give up my job for anything, but sometimes I just wish that the day were a little longer, or that I or the kids didn't need quite as much sleep to be sane the next morning.

Before you ask: yes, I changed my picture on the sidebar. I just couldn't handle how smugly superior I looked in the other picture, like I was gazing down from my throne on high. (Granted, this effect was probably amplified by the fact that Cal took the photo--Cal, who necessarily takes every portrait shot from below.) But every time I opened my own page, I felt like there I was, looking down my nose at my own self for wearing knock-off Keds in seventh grade or something. Remember when people used to color in little blue rectangles on the heels of their canvas sneakers, to make them look more like Keds? Yeah, me too. So anyway, I switched the photo. The surgical mask is not some sort of stab at anonymity, by the way--after almost ten years on the web, I think the cat's out of the bag on that one. It's just that that's the most recent photo I have of myself and I happened to take it at work, so there you are.

(Cal just came in as I was posting up that photo, by the way, and the following dialogue took place:

CAL

Is that a picture of you?

MICHELLE

Yeah, that's me.

CAL

You don't look normal.

MICHELLE

I look abnormal?

CAL

Yeah, why are you wearing that doctor suit?

Anyway, ha.)

As most people with jobs in medicine (and as probably most working mothers regardless of chosen career) can attest--my day to day life is pretty stressful. Not that I don't love my job, but there are moments when I consider the wisdom of choosing a field where patients routinely try to die right in front of my eyes. In those moments, I can appreciate the allure of a field like, say, pathology. Meticulous attention to details, beautiful grasp of descriptive vocabulary, and that certain distance between you and your patients that can sometimes be a saving grace. Granted, I think most people think that anesthesiologists already have enough distance from their patients (for instance, we always have ways to stop an annoying conversation--a syringe of midazolam in one hand and a syringe of propofol in the other does wonders), but I think most anesthesiologists that I've met are fairly empathic and have a decent bedside manner--or at the bare minimum have perfected the fine art of small talk--considering that the majority of their job takes place while the patient is unconscious.

If I had to list the most stressful thing in my life though, it would not be my job itself. In fact, far and away, I would say that the most stressful thing in my life is the juggle of trying to figure out who is going to be home for my kids in the evening. As an anesthesiologist, my hours are somewhat more variable than Joe's. Some days I get out from work pretty early, and some days I get out from work pretty late, and though for the most part I can anticipate which ones the Really Early and Really Late days are going to be, there are many days in between that I just don't know whether or not I'm going to be home by dinner until it's pretty much too late to do anything about it if I can't. These are the stress days.

We have a nanny and she's wonderful, and while she doesn't cook, I usually do enough cooking on the weekends that she has plenty of options of food to heat up and serve the kids. This particular nanny has been with us for two years now, so the kids know her and love her, and she has no problem staying with them until either Joe and I get home, even if it's a little later than expected, so thank goodness for that. But there are days when I'm trapped at work, and I get a text from Joe that he's trapped at work, and I think about the evening ticking by with neither parent at home, and all things that need to get done when we do return--the bathing and the school lunch-packing and the bed-timing and all of it--and it just stresses me out.

Oddly, being at work late in and of itself is not stressful at all if I know that Joe is home with the kids. In that way, my nights on call are oddly liberating. When I'm scheduled to be on call, Joe tries to structure his day so he can at least be home before 6:00pm, and once he texts me that he just walked in the door, I can relax. After that point, it feels like it doesn't matter how late I have to stay at the hospital. A parent has has landed. My kids are no longer orphans. And strange as it sounds, there are nights at the hospital that feel less frenzied and less stressful that certain evenings at home.

This is not to make parenthood seem like this joyless dirge of endless food preparation and cleaning up in various forms (though...kind of), and not to say that we don't have fun when we are home. We do. But sometimes the time we have together seems so short, and so goal-oriented, so purpose-driven. I wouldn't give up my job for anything, but sometimes I just wish that the day were a little longer, or that I or the kids didn't need quite as much sleep to be sane the next morning.

shear forces

I cut both kids' hair now myself, as some of you may know. Just some scissors around the ears, trim up the nape, and couple of different settings on the buzzers, and you have yourself one well-shorn kid. ("It shows your ears more." Remember that, from "My So-Called Life?" I loved that show. Even now, watching the show as an older person, I find myself sympathizing with Graham and Patty and wanting more to grab Angela by the shoulders and shake her to get her to stop being so mopey, for the love of God--a kind of reversal in empathy which I find moderately alarming, like I'm one of them now.)

(And by "them" I mean "the olds.")

Cal is now completely cooperative when getting his hair cut, though I have to admit that the start of my adventures into barbery (that's not a word, is it? To barber?) were incited by the fact that he acted like the barber was cutting off his damn fingers instead of his hair, despite all the usual kiddie barber enticements (TV, lollipops, chair shaped like a train). Anyway, Cal would probably be OK with a regular salon haircut now, but I'm pretty good at cutting his hair by this point and I work for free, so Tally Ho!

Mack is still in the phase where he apparently thinks that hair has nerve endings in it, though, so when I cut it this morning, I figured I'd go a little shorter than last time, so as to prolong the interval between now and the next forced grooming. It's possible, however, that I may have gone a little too far.

I mean, don't get me wrong, he's lost the matted-down sweaty chunks look that he's been sporting all summer, and thank goodness for that, but the reason I've been leaving his hair longer than Cal's is because I feel like babies look more babyish when their hair is longer. Every time I cut Mack's hair, even a little bit, he looks like he ages another six months. And now he looks like a Private First Class on the U.S.S. Pittsburgh.

I'm on call this weekend, by the way. Nothing like taking home call to make you feel like your cell phone is some grade of time bomb. Don't cut the blue wire!

I cut both kids' hair now myself, as some of you may know. Just some scissors around the ears, trim up the nape, and couple of different settings on the buzzers, and you have yourself one well-shorn kid. ("It shows your ears more." Remember that, from "My So-Called Life?" I loved that show. Even now, watching the show as an older person, I find myself sympathizing with Graham and Patty and wanting more to grab Angela by the shoulders and shake her to get her to stop being so mopey, for the love of God--a kind of reversal in empathy which I find moderately alarming, like I'm one of them now.)

(And by "them" I mean "the olds.")

Cal is now completely cooperative when getting his hair cut, though I have to admit that the start of my adventures into barbery (that's not a word, is it? To barber?) were incited by the fact that he acted like the barber was cutting off his damn fingers instead of his hair, despite all the usual kiddie barber enticements (TV, lollipops, chair shaped like a train). Anyway, Cal would probably be OK with a regular salon haircut now, but I'm pretty good at cutting his hair by this point and I work for free, so Tally Ho!

Mack is still in the phase where he apparently thinks that hair has nerve endings in it, though, so when I cut it this morning, I figured I'd go a little shorter than last time, so as to prolong the interval between now and the next forced grooming. It's possible, however, that I may have gone a little too far.

I mean, don't get me wrong, he's lost the matted-down sweaty chunks look that he's been sporting all summer, and thank goodness for that, but the reason I've been leaving his hair longer than Cal's is because I feel like babies look more babyish when their hair is longer. Every time I cut Mack's hair, even a little bit, he looks like he ages another six months. And now he looks like a Private First Class on the U.S.S. Pittsburgh.

I'm on call this weekend, by the way. Nothing like taking home call to make you feel like your cell phone is some grade of time bomb. Don't cut the blue wire!

correspondence

So the reason that my favorite medical books have been on my mind recently is that, like I mentioned before, my editor has been sending out advance copies of my book for people to blurb. Early responses have been pretty good (no book burnings yet that I'm aware of, at least), and so I've been trying to put together a fantasy wish list of all the people I would love to take a peek at the manuscript before it comes out. Certainly if any of the authors on my top five list even leafed through my book (yes, I know Randy Shiltz died, but, you know, the alive ones), my head would explode with happiness, and it seems unbelievable to me that something I wrote might possibly be looked over by these authors whose works I've read and loved for years.

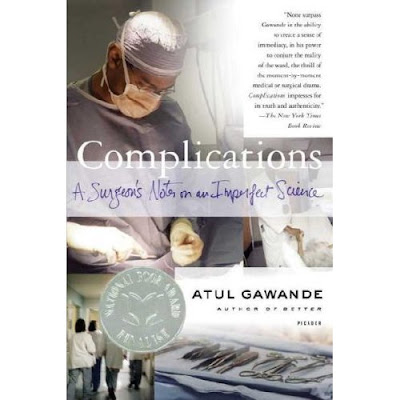

My editor feels like personal note tucked in with the advance copies might be that extra touch that adds so much (as opposed to a my-people-will-call-your-people sort of situation, I guess...not that I have people, but I'm sure the other authors do, because they are famous and also AWESOME) which is why I've been writing fan letters to Anne Fadiman and Atul Gawande. And also why I finally got some personal stationery. I have been writing notes on ripped out pieces of notebook paper for far too long, but now I am thirty-two years old, which seems like an age that having plain notecards with your name printed across the top might no longer be exceptional, but expected.

So the reason that my favorite medical books have been on my mind recently is that, like I mentioned before, my editor has been sending out advance copies of my book for people to blurb. Early responses have been pretty good (no book burnings yet that I'm aware of, at least), and so I've been trying to put together a fantasy wish list of all the people I would love to take a peek at the manuscript before it comes out. Certainly if any of the authors on my top five list even leafed through my book (yes, I know Randy Shiltz died, but, you know, the alive ones), my head would explode with happiness, and it seems unbelievable to me that something I wrote might possibly be looked over by these authors whose works I've read and loved for years.

My editor feels like personal note tucked in with the advance copies might be that extra touch that adds so much (as opposed to a my-people-will-call-your-people sort of situation, I guess...not that I have people, but I'm sure the other authors do, because they are famous and also AWESOME) which is why I've been writing fan letters to Anne Fadiman and Atul Gawande. And also why I finally got some personal stationery. I have been writing notes on ripped out pieces of notebook paper for far too long, but now I am thirty-two years old, which seems like an age that having plain notecards with your name printed across the top might no longer be exceptional, but expected.

suboptimal

Well we got in off the waitlist for an appointment with the dentist today, and I took extra call this Sunday night in order to be able to take him, but anyway, Cal got his cavity taken care of. It was...kind of terrible.

They did it with nitrous and local, and I think it was a sub-total block, because he was real good up until they started doing the pulpotomy, at which point he started screaming how much it hurt, and they had to call in two nurses to hold him down. I was waiting outside the door (per practitioner request), but basically bullied myself in when I heard the screaming. I know it sounds pretty barbaric, and it looked that way to eyewitnesses on the scene (that is to say: me), but I appreciate the fact that once they started getting into the pulp, no matter how much Cal was struggling, the important thing is to get in and get out with as much expediency as possible. However, I have to say that as an anesthesiologist, who every day lays hands on the tools and the meds that could have made things better, having to watch this particular procedure on this particular patient under suboptimal anesthesia was no less than psychological torture. It kind of reminded me of...what's that Greek myth with the guy who has to be thirsty for eternity, and every time he reaches down to get a drink of water from the pond he's standing in, the water line recedes? Oh right: Tantalus. It was like that. I knew exactly what I would have to do to stop my own child from freaking out in pain, and I had absolutely no means nor authority to do it. Again I say: torture.

Anyway, they at least did the pulpotomy (which, despite it all, I'm glad they did--still remains to be seen if there was an abscess but it was at least pre-abscess stage), and he has a temporary filling in place. The rest of the dental work, which consists of the permanent crown and two smaller fillings, will be completed with a Pediatric Anesthesiologist and IV sedation. And of that I am grateful. Cal seems to have recovered nicely from the experience and is running around as we speak (I started pushing Motrin basically the second he was out of the chair and will continue it round the clock for at least 24 hours, in an attempt to at least tamp down the inflammation to a low roar) but I will need some counseling for the PTSD. Parents of chronically ill kids, I don't know how you get through it all.

Anyway, after we left the dentist, I kept Cal out from school for the rest of the day (it was already noon, so whatever), and then took him to the toy store with basically blank check privileges to get whatever damn thing he wanted. And I don't care how overpriced it was. (Though: Playmobil, you are overpriced! OK, now I said it. I'm good.)

We'll be back at the dentist in a month and a half to finish the job with an actual anesthesiologist on hand. Anesthesia saves the day again, I guess.

Well we got in off the waitlist for an appointment with the dentist today, and I took extra call this Sunday night in order to be able to take him, but anyway, Cal got his cavity taken care of. It was...kind of terrible.

They did it with nitrous and local, and I think it was a sub-total block, because he was real good up until they started doing the pulpotomy, at which point he started screaming how much it hurt, and they had to call in two nurses to hold him down. I was waiting outside the door (per practitioner request), but basically bullied myself in when I heard the screaming. I know it sounds pretty barbaric, and it looked that way to eyewitnesses on the scene (that is to say: me), but I appreciate the fact that once they started getting into the pulp, no matter how much Cal was struggling, the important thing is to get in and get out with as much expediency as possible. However, I have to say that as an anesthesiologist, who every day lays hands on the tools and the meds that could have made things better, having to watch this particular procedure on this particular patient under suboptimal anesthesia was no less than psychological torture. It kind of reminded me of...what's that Greek myth with the guy who has to be thirsty for eternity, and every time he reaches down to get a drink of water from the pond he's standing in, the water line recedes? Oh right: Tantalus. It was like that. I knew exactly what I would have to do to stop my own child from freaking out in pain, and I had absolutely no means nor authority to do it. Again I say: torture.

Anyway, they at least did the pulpotomy (which, despite it all, I'm glad they did--still remains to be seen if there was an abscess but it was at least pre-abscess stage), and he has a temporary filling in place. The rest of the dental work, which consists of the permanent crown and two smaller fillings, will be completed with a Pediatric Anesthesiologist and IV sedation. And of that I am grateful. Cal seems to have recovered nicely from the experience and is running around as we speak (I started pushing Motrin basically the second he was out of the chair and will continue it round the clock for at least 24 hours, in an attempt to at least tamp down the inflammation to a low roar) but I will need some counseling for the PTSD. Parents of chronically ill kids, I don't know how you get through it all.

Anyway, after we left the dentist, I kept Cal out from school for the rest of the day (it was already noon, so whatever), and then took him to the toy store with basically blank check privileges to get whatever damn thing he wanted. And I don't care how overpriced it was. (Though: Playmobil, you are overpriced! OK, now I said it. I'm good.)

We'll be back at the dentist in a month and a half to finish the job with an actual anesthesiologist on hand. Anesthesia saves the day again, I guess.

teeth: the cause of, and solution to, all life's problems

So Cal needs a root canal.

The dentist calls it a "pulpotomy and a baby cap," but I figure anything that involves drilling and reaming out of pulp and covering with a little tooth hat sounds close enough to a root canal to me. I'm not sure how it quite got this far--I mean, we don't have the Sonicare toothbrush and a water pick, but we do, you know, brush his teeth twice a day and all try not to pack his molars with caramels or anything. But a few weeks ago Cal started complaining that one of his back teeth was hurting and I took him to the dentist and now here we are.

Cal has not notoriously been great with doctors (I blame poetic justice) but now that he's five and is at least approaching the age of reason, some combination of preparation and rationalization will temper the flight-or-flight response that typically characterized his medical interactions between the ages of two and four-and-a-half. Meaning he understands the need for doctors (occasionally) and will even comply with their exams, but when the pointy things start coming out, may the good lord help us all. Which is why I'm not really feeling great about the prospect of this root canal.

However, we're going to a pediatric dentist, and that helps immensely. Not only are they much more accustomed to dealing with kids (dur) but they have all sorts of enticements and incentives to get the kids to comply with their picking and drilling. I counted a total of four giant flat screen TVs playing all Pixar all the time, and that along with the embarrassment of riches that was the reward rack. (Strangely, the "treat" that captivated Cal the most was the new toothbrush and mini toothpaste, though certainly there were stickers and erasers and other tchotchkes that I'm still finding underfoot.) They made sure his first visit was a benign one, with just a tooth cleaning and X-rays, but obviously the next time we go we're going to have to Get Down To Business and I'm just not sure how that's going to fly.

However, to his (and their) credit, Cal did tremendously well the last time we were there (see the above picture, and his feigned nonchalance with the hand behind his head), and they say they use a little low-grade nitrous for sedation, at least during the local injection, so that's as much as I could ask for, I suppose. Actually, what I would ask for would be a pediatric anesthesiologist and a propofol infusion, but I will take what I can get.

So Cal needs a root canal.

The dentist calls it a "pulpotomy and a baby cap," but I figure anything that involves drilling and reaming out of pulp and covering with a little tooth hat sounds close enough to a root canal to me. I'm not sure how it quite got this far--I mean, we don't have the Sonicare toothbrush and a water pick, but we do, you know, brush his teeth twice a day and all try not to pack his molars with caramels or anything. But a few weeks ago Cal started complaining that one of his back teeth was hurting and I took him to the dentist and now here we are.

Cal has not notoriously been great with doctors (I blame poetic justice) but now that he's five and is at least approaching the age of reason, some combination of preparation and rationalization will temper the flight-or-flight response that typically characterized his medical interactions between the ages of two and four-and-a-half. Meaning he understands the need for doctors (occasionally) and will even comply with their exams, but when the pointy things start coming out, may the good lord help us all. Which is why I'm not really feeling great about the prospect of this root canal.

However, we're going to a pediatric dentist, and that helps immensely. Not only are they much more accustomed to dealing with kids (dur) but they have all sorts of enticements and incentives to get the kids to comply with their picking and drilling. I counted a total of four giant flat screen TVs playing all Pixar all the time, and that along with the embarrassment of riches that was the reward rack. (Strangely, the "treat" that captivated Cal the most was the new toothbrush and mini toothpaste, though certainly there were stickers and erasers and other tchotchkes that I'm still finding underfoot.) They made sure his first visit was a benign one, with just a tooth cleaning and X-rays, but obviously the next time we go we're going to have to Get Down To Business and I'm just not sure how that's going to fly.

However, to his (and their) credit, Cal did tremendously well the last time we were there (see the above picture, and his feigned nonchalance with the hand behind his head), and they say they use a little low-grade nitrous for sedation, at least during the local injection, so that's as much as I could ask for, I suppose. Actually, what I would ask for would be a pediatric anesthesiologist and a propofol infusion, but I will take what I can get.

pen nerds, unite! take back the night!

You may have noticed (though certainly the misguided companies that e-mail me soliciting product endorsements have not) that I do not run ads on this site. Never have. Sometimes I have used a free service that ran sidebar ads as part of their own business plan (Haloscan comes to mind--I used their service to run my comments section until that company imploded) but overall, I have never accepted money in exchange for ads or endorsements of any kinds. The only kind of endorsements I give--see the last blog entry, for instance--are ones that I do for free, in the spirit of a friend recommending something to a friend.

I know a lot of blogs--in fact, the majority of blogs--run some kind of ads to support themselves, and that is all good and fair. The reason I have chosen not to is multifactorial. First, this is a personal blog which happens to be written by a doctor. Corporate sponsorship is not necessary, nor would it necessarily be appropriate. Secondly, I need to keep things simple, as I have a hard enough time updating this blog as it is without thinking of peripherals like ad content and sidebars. Third, I have a job that pays the bills, and it's not worth it to me to run clutter-y, annoying ads in order to make whatever pittance in ad revenue I could generate.

So please just treat the following is a public service for pen nerds everywhere.

Full disclosure: after I talked about ordering from Jet Pens a few months ago, a representative from the company mailed me an envelope full of samples. I did not solicit the samples nor am I getting kickbacks from Jet Pens, but let it be known that I scroll through that Jet Pens website the way I page through the Ikea catalogue: pure visual porn.

First up, the Pilot Hi-Tec-C Coleto

Jet Pens very kindly sent a pen barrel along with three 0.4mm ink cartridges in the standard red, black and blue, though certainly for those more adventurous of us there are many more colors available. (For instance, a choice between "Orange" and "Apricot Orange." It's the subtle differences.) The pen is easy to use and very standard as multi-barrel pens go--just jam the ink cartridges in, press down what color you want to use, and start diagramming that Krebs cycle, you multicolor pen nerd, you. I had bought a few of the regular Pilot Hi-Tec-Cs to use before, and I did like the pen, although the pen tip was a little scratchy for me (my own fault, 0.4mm is a very fine tip) and the fact that it was a pen with an actual cap rather than a retractable pen drove me crazy.

People seem to rave about the Hi-Tec-C Coleto, as it gets past two of the commonly voiced displeasures about the regular Hi-Tec-C, in that 1.) it's retractable, and 2.) as multi-cartridge pen, the pen barrel itself is thicker and therefore easier to grip. However, two problems with the Coleto that I noticed were that there seemed to be a lot of "wiggle" of the cartridge within the barrel of the pen, to the point that it kind of affected my handwriting. To be fair, it's a very thin cartridge with a needle tip nib, and I do tend to push hard when I write, so perhaps it's operator dependent. However, with my personal writing style, I think I would find it too scratchy and too delicate for heavy use.

Next up, the Sarasa Zebra Clip Gel Ink Pen in Blue-Black with an 0.4mm tip

I'd eyed this pen before, because unlike many of the rarer Japanese or Korean imports (which makes it sound like we're talking about rare anime reel-to-reels or something, but no, WE'RE STILL TALKING ABOUT PENS) this pen is actually available at Staples. My source at Jet Pens also tells me that the clip (it is spring-loaded, which makes it open and close wider than the standard pen clip) has made it popular among nurses. I also liked this pen because it's retractable (cannot emphasize the importance of this feature--I refuse to use a pen at work if it is not retractable) and it has a nice rubber grip which makes it comfortable to hold.

It's a fine pen. It writes smoothly, the gel is nice and non-blobby, it looks like it has a decent ink supply, and didn't skip even after a couple of test drops from a respectable height. (The skipping gel pen is a major pet peeve. I drop my pens a lot, due to, you know, the Earth's gravity; and I cannot tell you how many 0.5mm Pilot G2s I've had in my life that just stopped working despite a full ink cartridge because I dropped them once or twice. HATE.) However, it's nothing special. And at two bucks each, they're fifty cents more than the Uni-ball Signo RT UM-138, which is a gorgeous fine tipped pen, with many of the same properties and (I think) a more handsome design. True, no springy clip, but I have not yet evidenced need for a springy-clip pen in my life to this point, so for my money, I'll stick with the Uni-balls.

(Also impressive about the RT-138s is that one time I had an anesthesia record that I got pretty wet--got sprayed with saline or something. The ink barely smeared. I have rubbed my writing with a latex glove bare seconds after laying down the line, and nary a smudge. That's a good hospital pen, friends.)

OK, one last review: the Pentel Sliccies Gel Ink Multi-Pen

Again, a multi-pen with 0.4mm tip, only the Pentel multi holds two cartridges, not three. The barrel is clear plastic, nothing fancy that you'd use to sign the Declaration of Independence or anything, but cheap enough that you wouldn't cry if you lost it. Easy to use, a large range of colors (in the blue spectrum we have blue, blue black, sky blue, and milk blue...yes, I said milk blue). One benefit of the Sliccies over the Hi-Tec-C is that the ink supply seems a little wetter somehow, which I like--makes the pen glide over the paper easier. However, again, the ink cartridge is small (probably a commonality among most multi-pens, just for mechanical reasons) so I'd be worried about running out of ink constantly. I guess I'm just not a multi-pen kind of person.

Oh, and unrelated to Jet Pens, I got a few of these guys yesterday:

You may have noticed (though certainly the misguided companies that e-mail me soliciting product endorsements have not) that I do not run ads on this site. Never have. Sometimes I have used a free service that ran sidebar ads as part of their own business plan (Haloscan comes to mind--I used their service to run my comments section until that company imploded) but overall, I have never accepted money in exchange for ads or endorsements of any kinds. The only kind of endorsements I give--see the last blog entry, for instance--are ones that I do for free, in the spirit of a friend recommending something to a friend.

I know a lot of blogs--in fact, the majority of blogs--run some kind of ads to support themselves, and that is all good and fair. The reason I have chosen not to is multifactorial. First, this is a personal blog which happens to be written by a doctor. Corporate sponsorship is not necessary, nor would it necessarily be appropriate. Secondly, I need to keep things simple, as I have a hard enough time updating this blog as it is without thinking of peripherals like ad content and sidebars. Third, I have a job that pays the bills, and it's not worth it to me to run clutter-y, annoying ads in order to make whatever pittance in ad revenue I could generate.

So please just treat the following is a public service for pen nerds everywhere.

Full disclosure: after I talked about ordering from Jet Pens a few months ago, a representative from the company mailed me an envelope full of samples. I did not solicit the samples nor am I getting kickbacks from Jet Pens, but let it be known that I scroll through that Jet Pens website the way I page through the Ikea catalogue: pure visual porn.

First up, the Pilot Hi-Tec-C Coleto

Jet Pens very kindly sent a pen barrel along with three 0.4mm ink cartridges in the standard red, black and blue, though certainly for those more adventurous of us there are many more colors available. (For instance, a choice between "Orange" and "Apricot Orange." It's the subtle differences.) The pen is easy to use and very standard as multi-barrel pens go--just jam the ink cartridges in, press down what color you want to use, and start diagramming that Krebs cycle, you multicolor pen nerd, you. I had bought a few of the regular Pilot Hi-Tec-Cs to use before, and I did like the pen, although the pen tip was a little scratchy for me (my own fault, 0.4mm is a very fine tip) and the fact that it was a pen with an actual cap rather than a retractable pen drove me crazy.

People seem to rave about the Hi-Tec-C Coleto, as it gets past two of the commonly voiced displeasures about the regular Hi-Tec-C, in that 1.) it's retractable, and 2.) as multi-cartridge pen, the pen barrel itself is thicker and therefore easier to grip. However, two problems with the Coleto that I noticed were that there seemed to be a lot of "wiggle" of the cartridge within the barrel of the pen, to the point that it kind of affected my handwriting. To be fair, it's a very thin cartridge with a needle tip nib, and I do tend to push hard when I write, so perhaps it's operator dependent. However, with my personal writing style, I think I would find it too scratchy and too delicate for heavy use.

Next up, the Sarasa Zebra Clip Gel Ink Pen in Blue-Black with an 0.4mm tip

I'd eyed this pen before, because unlike many of the rarer Japanese or Korean imports (which makes it sound like we're talking about rare anime reel-to-reels or something, but no, WE'RE STILL TALKING ABOUT PENS) this pen is actually available at Staples. My source at Jet Pens also tells me that the clip (it is spring-loaded, which makes it open and close wider than the standard pen clip) has made it popular among nurses. I also liked this pen because it's retractable (cannot emphasize the importance of this feature--I refuse to use a pen at work if it is not retractable) and it has a nice rubber grip which makes it comfortable to hold.

It's a fine pen. It writes smoothly, the gel is nice and non-blobby, it looks like it has a decent ink supply, and didn't skip even after a couple of test drops from a respectable height. (The skipping gel pen is a major pet peeve. I drop my pens a lot, due to, you know, the Earth's gravity; and I cannot tell you how many 0.5mm Pilot G2s I've had in my life that just stopped working despite a full ink cartridge because I dropped them once or twice. HATE.) However, it's nothing special. And at two bucks each, they're fifty cents more than the Uni-ball Signo RT UM-138, which is a gorgeous fine tipped pen, with many of the same properties and (I think) a more handsome design. True, no springy clip, but I have not yet evidenced need for a springy-clip pen in my life to this point, so for my money, I'll stick with the Uni-balls.

(Also impressive about the RT-138s is that one time I had an anesthesia record that I got pretty wet--got sprayed with saline or something. The ink barely smeared. I have rubbed my writing with a latex glove bare seconds after laying down the line, and nary a smudge. That's a good hospital pen, friends.)

OK, one last review: the Pentel Sliccies Gel Ink Multi-Pen

Again, a multi-pen with 0.4mm tip, only the Pentel multi holds two cartridges, not three. The barrel is clear plastic, nothing fancy that you'd use to sign the Declaration of Independence or anything, but cheap enough that you wouldn't cry if you lost it. Easy to use, a large range of colors (in the blue spectrum we have blue, blue black, sky blue, and milk blue...yes, I said milk blue). One benefit of the Sliccies over the Hi-Tec-C is that the ink supply seems a little wetter somehow, which I like--makes the pen glide over the paper easier. However, again, the ink cartridge is small (probably a commonality among most multi-pens, just for mechanical reasons) so I'd be worried about running out of ink constantly. I guess I'm just not a multi-pen kind of person.

Oh, and unrelated to Jet Pens, I got a few of these guys yesterday:

(It's the Pilot Precise V7 RT, in case you don't have your bifocals on.)

I usually don't like writing in a 0.7mm tip, because I prefer a more precise line and anything too thick tends to blob up on me. But I had to write a letter to someone and I knew that if I used my standard 0.38mm pen (I have them in both the Uni-ball Signo RT UM-138 as well as the Pilot G2s, which you can find in 0.38mm at your regular big box office supply store if you look hard enough) then my writing would be too small. The Pilot Precise V7 RT really fit the bill. It's a fatter, wetter line, but great for scrawling larger notes, and makes signing your name feel awesome. The one caveat with this pen is that it does tend to smudge and bleed quite a bit on the wrong kind of paper, or if your writing gets wet, so perhaps more for your correspondence than for writing in the hospital.

I should get a show on NPR where I just talk about pens. And then I could squawk at my co-host in an abrasive Boston accent and make corny Dad-jokes. Oh wait, that's "Car Talk." Still, if anyone has a programming slot on their local public radio station, call me. As demonstrated, I can talk about pens for a long time.

(Idle aside: my dream--and I think it's a stretch, though not impossible--is to be invited to be a guest on "Jordan, Jesse, Go!" Yes, now you know that my self-professed life's goal is to be featured as a one-time guest on a marginally well-known niche comedy podcast. I REACH FOR THE STARS.)

I usually don't like writing in a 0.7mm tip, because I prefer a more precise line and anything too thick tends to blob up on me. But I had to write a letter to someone and I knew that if I used my standard 0.38mm pen (I have them in both the Uni-ball Signo RT UM-138 as well as the Pilot G2s, which you can find in 0.38mm at your regular big box office supply store if you look hard enough) then my writing would be too small. The Pilot Precise V7 RT really fit the bill. It's a fatter, wetter line, but great for scrawling larger notes, and makes signing your name feel awesome. The one caveat with this pen is that it does tend to smudge and bleed quite a bit on the wrong kind of paper, or if your writing gets wet, so perhaps more for your correspondence than for writing in the hospital.

I should get a show on NPR where I just talk about pens. And then I could squawk at my co-host in an abrasive Boston accent and make corny Dad-jokes. Oh wait, that's "Car Talk." Still, if anyone has a programming slot on their local public radio station, call me. As demonstrated, I can talk about pens for a long time.

(Idle aside: my dream--and I think it's a stretch, though not impossible--is to be invited to be a guest on "Jordan, Jesse, Go!" Yes, now you know that my self-professed life's goal is to be featured as a one-time guest on a marginally well-known niche comedy podcast. I REACH FOR THE STARS.)

like oprah's book club without the oprah

My youngest sister (she's ten years younger than me, which either makes her very young or me very old, I'll choose the former) is starting medical school in the fall. I think there is a certain futility in giving medical students or pre-medical students advice outside of the purely practical--never pass up a free meal, sleep when you can, that kind of thing--because there are certain things that you will never, ever believe, and certain lessons that you will not be ready to absorb until you've gone through the experience of learning them firsthand. In that sense, medical school is much like that final scene in Oz (as in "The Wizard of Oz," not the HBO series set in prison with all the riots and butt-raping) where the scarecrow asks the Good Witch of the North:

SCARECROW

Then why didn't you tell her before?

GLINDA

Because she wouldn't have believed me. She had to learn it for herself.

Medical students, there are things that I can tell you about medicine, but you'll never believe me. You'll just have to learn them for yourselves. However, let it not be said that I didn't try.

Therefore, I would like to now present to you my list of the five books I think that every student should read before starting medical training, be it for your MD, DO, PA, nursing degree, or what have you. Note that my own book is not among them, though if you would like to read it nonetheless when it comes out, I certainly wouldn't dissuade you.

* * *

1. The Spirit Catches You And You Fall Down (by Anne Fadiman)

The story of a young first-generation Hmong girl with epilepsy, her interface with the American healthcare system, and the catastrophic culture clash that ensued. I read a review that called this a tragedy of Shakespearean proportions, and I think that's pretty much right on the money. I also think this is one of the best books about the medicine I have ever read. Sensitive and beautifully written, this book dares you to choose sides, turns your expectations inside-out, and showed me more than anything that medicine should be treated more like an art than a religion.

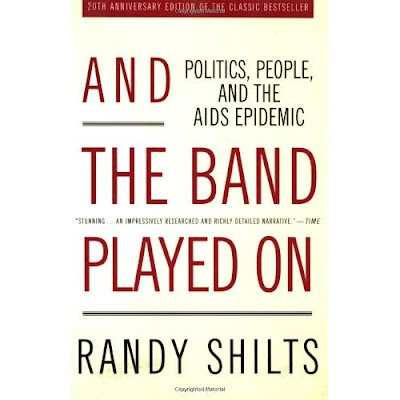

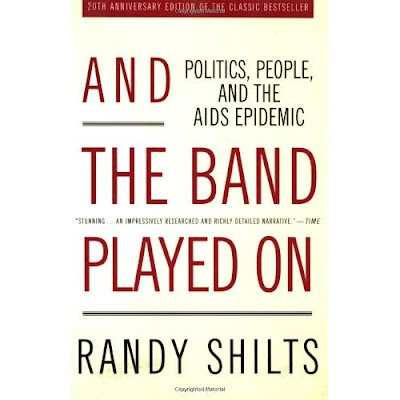

2. And The Band Played On (by Randy Shilts)

I first read this book I think in tenth grade, when I was writing a Social Studies paper about the history of the AIDS epidemic. (Grade on the paper: A minus, but this particular teacher was known for his grade inflation, so it probably was a pretty crappy paper. I do remember printing it out on my dot matrix printer as well, the sound of which always reminded me of sitting in a dentist's office.)

I know that for some people, just reading the subtitle, "Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic" is enough to send you to running for the door (or to say that it sounds like something you'd be assigned--read: forced--to read in some college Poli-Sci class), but hear me out. Written more than twenty years ago by Randy Shilts, who I believe since succumbed to the epidemic himself, it is a journalistic work to be sure, but written in such a way that can best be described as cinematic. It's an exciting book to read. It's a tragic book to read. AIDS has been part of our landscape for so long now it's hard to imagine living in a world before we even knew what the disease did, how it was spread, or that it was caused by a virus. The steps in the healthcare process, in the political process, the small acts of craven ignorance and everyday heroism depicted along the way are unforgettable. We live in a world now where AIDS is a household name. Everyone should read about this time not so long ago when it was not.

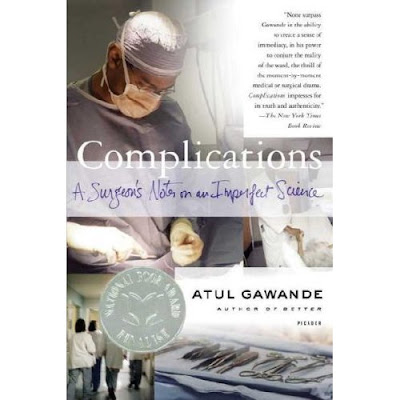

3. Complications (by Atul Gawande)

I'm pretty sure that by now I don't need to convince anyone that Atul Gawande is a great writer, but let me just say it again. He's a great writer. His writing is more process-oriented than personal, but I think some of the best parts of the book are the personal bits--the part where he talks about his first experience putting in a central line as an intern, the part where he talks about the decision process of choosing a surgeon for his own son, born with a congenital heart defect. Moreover, Gawande highlights his approach to medicine in his own subtitle, "A Surgeon's Notes on an Imperfect Science." Medicine is imperfect. We are imperfect. It is in acknowledging these imperfections and how we strive to be better than we already are that makes the difference.

4. Singular Intimacies (by Danielle Ofri)

I once heard a book editor complain about the glut of doctors who were pedaling around book proposals or manuscripts in various stages of completion about the medical training process. "Every doctor has stories," he said, "but not every doctor can write. The problem is, they don't know that." And I will freely admit to you, I have lived in fear ever since I heard that insider comment that I am yet another in a long line of doctors who has more stories to tell than the talent to tell them.

Danielle Ofri has stories, and she tells them well. This book is basically a memoir of a young doctor in training, starting with her days as a medical student up through her graduation from residency. Most of the chapters (more like vignettes) existed as standalone stories in one for or another; she was widely published in a variety of magazines prior to coming out with her first book, and is now the Editor-in-Chief and co-founder of the Bellevue Literary Review, which is a literary journal that publishes works related to medicine and health.

My youngest sister (she's ten years younger than me, which either makes her very young or me very old, I'll choose the former) is starting medical school in the fall. I think there is a certain futility in giving medical students or pre-medical students advice outside of the purely practical--never pass up a free meal, sleep when you can, that kind of thing--because there are certain things that you will never, ever believe, and certain lessons that you will not be ready to absorb until you've gone through the experience of learning them firsthand. In that sense, medical school is much like that final scene in Oz (as in "The Wizard of Oz," not the HBO series set in prison with all the riots and butt-raping) where the scarecrow asks the Good Witch of the North:

SCARECROW

Then why didn't you tell her before?

GLINDA

Because she wouldn't have believed me. She had to learn it for herself.

Medical students, there are things that I can tell you about medicine, but you'll never believe me. You'll just have to learn them for yourselves. However, let it not be said that I didn't try.

Therefore, I would like to now present to you my list of the five books I think that every student should read before starting medical training, be it for your MD, DO, PA, nursing degree, or what have you. Note that my own book is not among them, though if you would like to read it nonetheless when it comes out, I certainly wouldn't dissuade you.

* * *

1. The Spirit Catches You And You Fall Down (by Anne Fadiman)

The story of a young first-generation Hmong girl with epilepsy, her interface with the American healthcare system, and the catastrophic culture clash that ensued. I read a review that called this a tragedy of Shakespearean proportions, and I think that's pretty much right on the money. I also think this is one of the best books about the medicine I have ever read. Sensitive and beautifully written, this book dares you to choose sides, turns your expectations inside-out, and showed me more than anything that medicine should be treated more like an art than a religion.

I read this book early in my Pediatrics residency (long-time readers remember that I did two years of Peds before switching to Anesthesia) and it completely changed my life. I wish I could say that I remember the lessons from this book every day when I deal with my actual patients, but that's why it bears frequent re-reading; I must have read this book at least ten times in the past five years.

2. And The Band Played On (by Randy Shilts)

I first read this book I think in tenth grade, when I was writing a Social Studies paper about the history of the AIDS epidemic. (Grade on the paper: A minus, but this particular teacher was known for his grade inflation, so it probably was a pretty crappy paper. I do remember printing it out on my dot matrix printer as well, the sound of which always reminded me of sitting in a dentist's office.)

I know that for some people, just reading the subtitle, "Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic" is enough to send you to running for the door (or to say that it sounds like something you'd be assigned--read: forced--to read in some college Poli-Sci class), but hear me out. Written more than twenty years ago by Randy Shilts, who I believe since succumbed to the epidemic himself, it is a journalistic work to be sure, but written in such a way that can best be described as cinematic. It's an exciting book to read. It's a tragic book to read. AIDS has been part of our landscape for so long now it's hard to imagine living in a world before we even knew what the disease did, how it was spread, or that it was caused by a virus. The steps in the healthcare process, in the political process, the small acts of craven ignorance and everyday heroism depicted along the way are unforgettable. We live in a world now where AIDS is a household name. Everyone should read about this time not so long ago when it was not.

3. Complications (by Atul Gawande)

I'm pretty sure that by now I don't need to convince anyone that Atul Gawande is a great writer, but let me just say it again. He's a great writer. His writing is more process-oriented than personal, but I think some of the best parts of the book are the personal bits--the part where he talks about his first experience putting in a central line as an intern, the part where he talks about the decision process of choosing a surgeon for his own son, born with a congenital heart defect. Moreover, Gawande highlights his approach to medicine in his own subtitle, "A Surgeon's Notes on an Imperfect Science." Medicine is imperfect. We are imperfect. It is in acknowledging these imperfections and how we strive to be better than we already are that makes the difference.

4. Singular Intimacies (by Danielle Ofri)

I once heard a book editor complain about the glut of doctors who were pedaling around book proposals or manuscripts in various stages of completion about the medical training process. "Every doctor has stories," he said, "but not every doctor can write. The problem is, they don't know that." And I will freely admit to you, I have lived in fear ever since I heard that insider comment that I am yet another in a long line of doctors who has more stories to tell than the talent to tell them.

Danielle Ofri has stories, and she tells them well. This book is basically a memoir of a young doctor in training, starting with her days as a medical student up through her graduation from residency. Most of the chapters (more like vignettes) existed as standalone stories in one for or another; she was widely published in a variety of magazines prior to coming out with her first book, and is now the Editor-in-Chief and co-founder of the Bellevue Literary Review, which is a literary journal that publishes works related to medicine and health.

What strikes me most about Ofri's first book is her fearlessness in admitting her own failures, her own weaknesses, her own moments of doubt throughout the early years of her training. We've all been there, but not everyone can so nakedly capture that feeling that one has as a medical student, an intern, that first night as the senior resident on the floor, of "I-don't-quite-know-what-I'm-doing-but-now-I-have-to-pretend-like-I-do." In a world of medicine being depicted as large-than-life and heroic, her humanizing the scope of medical training is wonderful and refreshing.

5. Walk on Water (by Michael Ruhlman)

I've read this book many, many times, and each time, I can't put it down until I've read it cover-to-cover. Michael Ruhlman is a journalist (I think he may have been a sports writer in a prior incarnation) who spends several months with a team of pediatric cardiothoracic surgeons at the Cleveland Clinic, headed by chief surgeon Roger Mee.

5. Walk on Water (by Michael Ruhlman)

I've read this book many, many times, and each time, I can't put it down until I've read it cover-to-cover. Michael Ruhlman is a journalist (I think he may have been a sports writer in a prior incarnation) who spends several months with a team of pediatric cardiothoracic surgeons at the Cleveland Clinic, headed by chief surgeon Roger Mee.

Now, this may be the anesthesiologist in me speaking, but there's nothing I find more distasteful than the "Surgeon as God" narrative, and so I picked up this book with some hesitation. But this book is nothing like that. That is not to say that the surgical skill displayed is not remarkable (it is) or that the scenes in the OR are not heart-pounding (they are), or the stories of the tiniest lives saved not awe-inspiring (they totally are). But the bigger picture of this book is the evolution of medicine, how far we've come in such a short time, where we are now, and how much farther we still have to go when it comes to saving our youngest and sickest patients. It also marvels at the craft of medicine, the skill, and how to be the very, very best at a certain field, it takes more than just hard work and dogged persistence--in some ways, you have to be kind of a freak of nature. Roger Mee is very, very good at what he does, which is pediatric open-heart surgery, and therefore he feels it is his responsibility to do just that, whether he likes it or not.

(As an aside, I have to say that I trained in Pediatrics for two years, and worked in the PICU and NICU where I took care of scores of post-op complex congenital heart patients. However, there were certain passages in the book where Ruhlman, a layperson, discusses the physiology of the Fontan or the challenges of the Norwood, and I understood the surgery in far more clarity than any of the cardiologists or surgeons I'd worked with had ever been able to explain to me. He is a gifted writer, and speaks fluently in the foreign language of medicine. Bravo.)

* * *

There is one theme at the core of all these books, more overt in some than in others, but a central thread in all good medical non-fiction nonetheless. Which brings me back to my original point. If I could give young healthcare professionals one piece of advice, one word to live by, it would be this: humility. Be humble. Yes, all the standard advice still applies: work hard, sweat the details, treat your patients as you'd want your family to be treated--but I think humility is probably the most important quality for a young doctor, for any doctor to have.

Admit when you don't know something. Admit when you've failed. Admit when your goals exceed your reach, when the skills required exceed your experience, but never stop trying to push that limit. Know when to stop, know when to ask for help, and above all, be aware of your own limitations while trying constantly to exceed them. That's the most important thing in medicine. If you think you know everything there is to know, not only will you always be wrong, but you'll wall yourself off against learning anything new. So be humble. Know what it is that is just outside your reach, and spend your entire life trying to get there.

(As an aside, I have to say that I trained in Pediatrics for two years, and worked in the PICU and NICU where I took care of scores of post-op complex congenital heart patients. However, there were certain passages in the book where Ruhlman, a layperson, discusses the physiology of the Fontan or the challenges of the Norwood, and I understood the surgery in far more clarity than any of the cardiologists or surgeons I'd worked with had ever been able to explain to me. He is a gifted writer, and speaks fluently in the foreign language of medicine. Bravo.)

* * *

There is one theme at the core of all these books, more overt in some than in others, but a central thread in all good medical non-fiction nonetheless. Which brings me back to my original point. If I could give young healthcare professionals one piece of advice, one word to live by, it would be this: humility. Be humble. Yes, all the standard advice still applies: work hard, sweat the details, treat your patients as you'd want your family to be treated--but I think humility is probably the most important quality for a young doctor, for any doctor to have.

Admit when you don't know something. Admit when you've failed. Admit when your goals exceed your reach, when the skills required exceed your experience, but never stop trying to push that limit. Know when to stop, know when to ask for help, and above all, be aware of your own limitations while trying constantly to exceed them. That's the most important thing in medicine. If you think you know everything there is to know, not only will you always be wrong, but you'll wall yourself off against learning anything new. So be humble. Know what it is that is just outside your reach, and spend your entire life trying to get there.

(Any books to add to this list? Let us know in the comments section! For the five I picked here, there's another twenty I left out. What are your favorites?)

because i'm on vacation, that's why i'm updating all of a sudden

You would think (or at least: I would have thought, circa 2007) that having a book come out next year would be something that would be dominating my life right now. But it really isn't. Mostly because I've been working on this thing in one form or another for the better part of three years, and also mostly because the whole book publishing process is very deliberate and protracted, with lots of back and forth and this-department and that-department. Every once in a while I get a package or an e-mail with evidence that things have moved one click ahead (for example, last week I got to see some sample pages to solicit my opinion on things like fonts and stuff--ah, to be at the choosing fonts stage! It's every former high school newspaper editor's dream! I love choosing a good font.) but other than that, the book seems like something very peripheral to my everyday life. Not that's it's not exciting or cool, and not that I'm not dying to see the first bound copy or eagerly awaiting publication, but it just seems...peripheral. And, to be clear, my everyday life consists mainly of taking care of very sick patients, administering anesthesia, getting blood sprayed on me hither and yon, and then coming home, trying to create dinners out of thin air that bear at least a reasonable resemblance to the FDA's food pyramid, bathing two gross sweaty boy kids, wrangling them into their pajamas and then wresting them into bed (read: sitting witness at the bedside until they pass out from exhaustion or verbiage-induced asphyxiation). Rinse, repeat, repeat, repeat.

Where was I? Oh yes, the book.

The book, I think, is in the layout stage now. I don't know what this stage is actually called, but we're past the copyediting stage (aka the part where they send back your manuscript with a billion blue and green pencil marks, erupting Post-it Notes demanding clarification on this or that point--my editor attests that this is the cleanest manuscript she's seen in a while, but if so, I'd hate to see the sloppy ones) and at the typesetting phase, where they take the words and download them into book form. So hopefully, the next time I see this thing, it will at least somewhat resemble the bound and final manuscript, even if it isn't, you know, bound and finalized.

We're also at the early stages of soliciting blurbs. You have to forgive me if I'm not explaining this right, but I'm a neophyte as this, so I'm just explaining this process as I understand it myself, which is to say in a very rudimentary and peripheral way; but blurbs are short recommendations or insights about the book solicited from other writers or notables. Which is to say famous people. I'm sure there are certainly authors who have their share of famous friends, but as I was unfortunately not present at the Algonquin round table, my exposure to the literati past, present and future has been sadly lacking.

We're getting some great blurbs in, and advance attention has been positive, but I would think that when it comes to matter of publicity that more is better, so if you happen to know of any famous people who might be interested in receiving an advanced reviewer's copy of the book, I'm sure the good people at Grand Central Publishing would be more than happy to send one their way. E-mail me, won't you?

Also, yes I am off this week. This is one of the benefits of being in private practice anesthesia--I get more vacation time now, even if I don't really need it. But who am I kidding, I always need it. Did I tell you about that patient I had last week? Well, of course not, because of HIPAA, and me needing to not get fired. But believe me, it was intense.

Famous people who like to blurb books! E-mail me! I love you in advance!

You would think (or at least: I would have thought, circa 2007) that having a book come out next year would be something that would be dominating my life right now. But it really isn't. Mostly because I've been working on this thing in one form or another for the better part of three years, and also mostly because the whole book publishing process is very deliberate and protracted, with lots of back and forth and this-department and that-department. Every once in a while I get a package or an e-mail with evidence that things have moved one click ahead (for example, last week I got to see some sample pages to solicit my opinion on things like fonts and stuff--ah, to be at the choosing fonts stage! It's every former high school newspaper editor's dream! I love choosing a good font.) but other than that, the book seems like something very peripheral to my everyday life. Not that's it's not exciting or cool, and not that I'm not dying to see the first bound copy or eagerly awaiting publication, but it just seems...peripheral. And, to be clear, my everyday life consists mainly of taking care of very sick patients, administering anesthesia, getting blood sprayed on me hither and yon, and then coming home, trying to create dinners out of thin air that bear at least a reasonable resemblance to the FDA's food pyramid, bathing two gross sweaty boy kids, wrangling them into their pajamas and then wresting them into bed (read: sitting witness at the bedside until they pass out from exhaustion or verbiage-induced asphyxiation). Rinse, repeat, repeat, repeat.

Where was I? Oh yes, the book.

The book, I think, is in the layout stage now. I don't know what this stage is actually called, but we're past the copyediting stage (aka the part where they send back your manuscript with a billion blue and green pencil marks, erupting Post-it Notes demanding clarification on this or that point--my editor attests that this is the cleanest manuscript she's seen in a while, but if so, I'd hate to see the sloppy ones) and at the typesetting phase, where they take the words and download them into book form. So hopefully, the next time I see this thing, it will at least somewhat resemble the bound and final manuscript, even if it isn't, you know, bound and finalized.

We're also at the early stages of soliciting blurbs. You have to forgive me if I'm not explaining this right, but I'm a neophyte as this, so I'm just explaining this process as I understand it myself, which is to say in a very rudimentary and peripheral way; but blurbs are short recommendations or insights about the book solicited from other writers or notables. Which is to say famous people. I'm sure there are certainly authors who have their share of famous friends, but as I was unfortunately not present at the Algonquin round table, my exposure to the literati past, present and future has been sadly lacking.

We're getting some great blurbs in, and advance attention has been positive, but I would think that when it comes to matter of publicity that more is better, so if you happen to know of any famous people who might be interested in receiving an advanced reviewer's copy of the book, I'm sure the good people at Grand Central Publishing would be more than happy to send one their way. E-mail me, won't you?

Also, yes I am off this week. This is one of the benefits of being in private practice anesthesia--I get more vacation time now, even if I don't really need it. But who am I kidding, I always need it. Did I tell you about that patient I had last week? Well, of course not, because of HIPAA, and me needing to not get fired. But believe me, it was intense.

Famous people who like to blurb books! E-mail me! I love you in advance!

this kid is five years old

I know this is the most trite sentiment in the history of parenting but you have to forgive it because it's true; but one second I had a baby, and the next second, he became a kid.

Cal turned five a couple of weeks ago.

I know this is the most trite sentiment in the history of parenting but you have to forgive it because it's true; but one second I had a baby, and the next second, he became a kid.

Cal turned five a couple of weeks ago.

He's not even a preschooler anymore. He starts kindergarten this fall. Which, I think, is no longer considered preschool. He's a schooler. Schoolboy. Whatever.

I could get all sappy and sentimental here about how fast the time is going and how he was just a baby in my arms (I would sing this, of course, and all the while a guy in silhouette would be playing a violin on my roof) but frankly, his birthday was a couple of weeks ago, when I was too busy to write about it, so the sappiness has faded somewhat. It's still weird though. It's like suddenly, my kid became old. Which probably implies some ominous things for me. My telomeres are shortening as we speak!

It's weird, because day to day, I can't quite tell he's getting older, but when I look at his school pictures from last fall, I can see the changes. He's getting thinner. His face is getting longer. Sometimes I still see the baby. But sometimes I can see flashes of him as a teenager, and it's weird. He's going to be a good-looking man, am I right, ladies? I just hope he can get that scowl off his face by then. No one likes a brooder, Cal.

(I am lying. Many people inexplicably like brooders. Exhibit A: Jordan Catalano.)

That's better.

Happy belated birthday, Cal*. Now on to what's next.

* By "Happy belated birthday," I don't mean to say that we didn't actually celebrate his birthday when it happened. Because we did. We even had a birthday party. Nothing says "summer birthday" like a party at the municipal pool! Luckily none of the attendees threw up in the pool afterwards, because I think that the neon orange frosting on the Toy Story cupcakes** would have probably incriminated our group as flagrant disregarders of the "no swimming for 30 minutes after eating" rule.

** No, I didn't make the cupcakes. Because I didn't want anyone to die.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)